Hunting Opportunity is Not Always Equal – The Stormy Present

A story on how hunting privilege changes with the color of your skin.

The dogmas of the quiet past are inadequate to the stormy present. The occasion is piled high with difficulty and we must rise with the occasion. – Abraham Lincoln

One more sleep! I said.

Can’t wait! he replied.

It was the day before the pheasant opener. Perfect weather was in the forecast, and reports of good bird numbers were coming in from the locals. The next morning, we hopped in the truck and headed west. Then south.

Four hours later, we crossed the border. After a quick passport check and a peek at the dogs in the back, the officer waved us through. “Good luck!” he said as we pulled away.

Our next stop was to purchase shotgun shells at a big-box outdoor store an hour down the road. While browsing the gun racks, I noticed a cool looking rifle. It was a kind of gun I’d never handled before and I was curious to see what it was like, up close.

“Could I have a look at that rifle, the one on the left?”

“The AR-15? Sure, it’s used, but in excellent shape” said the guy behind the counter.

It was a sleek, well-balanced firearm that felt lighter than it looked. I shouldered it, aimed at a ceiling light. “Sweet!” I thanked the salesman and handed it back. “We’re on our way to hunt pheasants”.

“Good luck,” he replied.

We left the store and drove towards the interstate highway that would lead us to our destination, a motel in a small town in the middle of pheasant country. About a half mile from the on-ramp, I noticed blue lights flashing in my rearview mirror.

Cops.

“Good afternoon, officer.”

“Hi. I pulled you over because you have a rope or something hanging out of the back of your truck, dragging on the road.”

“Really? May I get out to have a look?”

“Yeah, step out.”

It was a check cord. It must have slipped through the space between the tailgate and bumper after we’d stopped to water the dogs. I opened the tailgate, pulled it in and put it in the drawer where it belongs. The officer checked my licence, registration and both our passports.

“Okay, guys, have a good day.”

“Thanks!” we said in unison.

Just before sundown we checked into our hotel and headed straight to a local restaurant for burgers and beers. Nothing better than mom and pop restaurant food after a long day of travelling. The next morning we drove straight to one of our favorite spots and let the dogs do their thing. By noon, we had a pair of roosters, each.

“Remember that spot we saw on our way down? We should go ask the farmer if we could hunt it.”

Twenty minutes later, after a brief chat on the doorstep of a friendly farmer’s home, we had permission to hunt about 100 acres of great looking pheasant cover. An hour after that, we were headed back to town. We’d limited out.

It’s a cool story, and in a way, perfectly ordinary.

Sure, limiting out on ring-necked pheasants is not something I actually do very often, but everything else in it reflects what, to me, is a very normal, ordinary experience as a hunter. I’ve crossed the U.S. border dozens of times, I’ve visited a ton of gun shops, I’ve been to motels, bars and restaurants all over the place and I’ve had friendly chats with a whole lot of friendly farmers. And yes, the police really did stop me once for a dangling check cord.

It’s a story of an ordinary hunt in an ordinary year. For me.

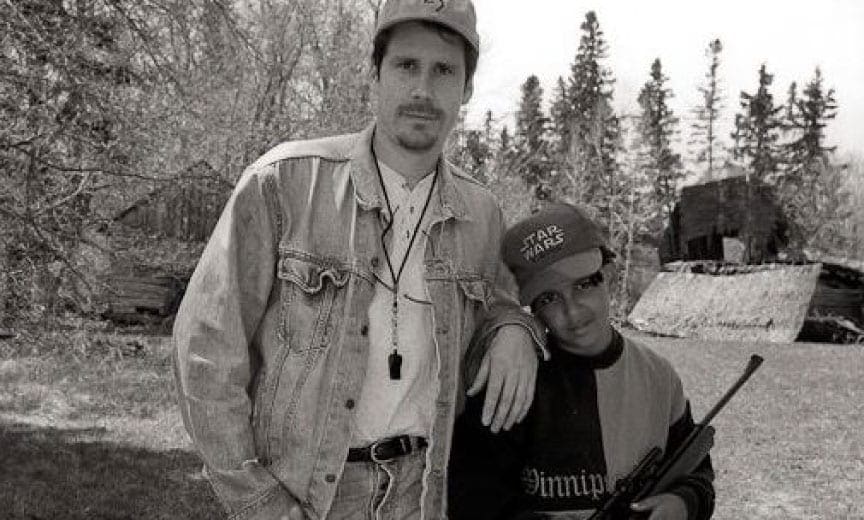

But for the other man in the story, my nephew, there is a good chance that the story wouldn’t be the same if he were alone. And it’s not because he’s younger, stronger and way more handsome than me.

It’s because he’s black.

I’m a middle-aged white man. My nephew is a young black man. Together, we’ve crossed the border, been stopped by the police, checked into a hotel, asked to see guns at a gunshop, and knocked on farmers’ doors, and we’ve never had a problem.

But what if we weren’t together? Would the story be the same? What if my nephew crossed the border in a pickup, with dogs and guns, alone? What if he asked to see an AR-15 at a gun shop, or was stopped by the police, or knocked on a farmer’s door, alone? Would the story be the same?

Before I sat down to write this piece I did a lot of soul searching, asking myself those very questions. And the answers I came up with broke my heart. And yesterday, when I asked my nephew about his experiences as a person of colour who just happens to love hunting and fishing, his answer confirmed my fears.

“I don’t really think about it much, probably because I always hunt with you and Auntie Lisa. And you guys are always the ones that ask for permission or deal with the border guards and all that. But to be perfectly honest, I wouldn’t feel comfortable doing some of those things on my own. And if my brother was with me or a couple of my black friends—no way.”

He and I are of the same blood. We have the same name—we’re Craig and Craig to our hunting friends. We grew up in the same neighbourhood, in the same city and together we’ve hunted the same coverts for over 20 years. But our experiences, as men, as hunters, as members of the upland hunting community can never really be the same.

Because the colour of our skin is not the same.

When I cross a border, knock on a farmer’s door, visit a gun shop or meet another hunter in the field, I feel no angst. Because as a white man, I’m exempt. My gender and skin colour give me an exemption from the anxieties that people of colour deal with every day. They immunize me to the effects of a virus that infects much of our world, the virus of discrimination.

But my nephew’s not exempt. He’s not immune. Because his skin is of a different colour.

Read: The Juxtaposition of Pride in Hunting

Over the last few days, I’ve heard from and read articles written by hunters of colour, of different orientations and genders and the main thing that stood out to me was that they all have to deal with a kind of angst that is completely unknown to me. The amount of angst varies of course. Some said it is mild, others admit that it is sometimes severe. But it is never zero for any of them.

Perhaps the most shocking example I read was in an article published on the MeatEater blog. Rick Dillard, a black man who loves to hunt, said: “I’ve had many black friends say there’s no way they’d go to unfamiliar places in the woods where they’d be the only black among a lot of white people they don’t know. When I go to Colorado with my friends to hunt, we’re probably the only black people on that mountain. Friends ask if I’m afraid being out there among all those white people with guns. I’m not, but it’s a real fear for many black people. It might be changing, but it’s there.”

When I mentioned the quote to my friend Durrell Smith, a young black man who’s just as crazy about bird dogs as I am, he said, “Yeah, I totally get that. When I go hunting I make sure I tell my wife exactly where I am going, who I am going with, what route we will take and when I will be back home.”

READ: Ambition to Tradition – Georgia-Florida Shooting Dog Handlers Club

But isn’t that what every hunter or hiker is supposed to do? I always let someone know where I’m going and when I will be back. After all, I could get lost, or my truck could break down. But for Durrell, in addition to the potential hazards of the field, he has a whole list of other things to worry about, things that never even cross my mind.

As a white man, I’m exempt. I’m spared the anxieties that people of colour deal with every day, immune to the virus of discrimination that still infects much of our world today. But Rick Dillard and Durrell Smith are not exempt. They are not immune. Because their skin is of a different shade.

As an armchair historian, whenever I sit down to write an article about dogs and hunting, I always look back to see what the past can teach us about the present. And, in this case, what we can learn is quite a lot, because much of it has been forgotten.

A few days ago A.J. DeRosa started a conversation in the Project Upland Facebook Community in which he described himself as a privileged white male. But being white and male doesn’t mean he’s automatically better off than others, or that he doesn’t have to work his ass off to succeed. It simply means that, like me, he’s exempt from the day-to-day anxieties that people of colour deal with all year round, on city streets and in the hunting field. At one point in the conversation, A.J. mentioned his grandfather, and that got me wondering if the white-male exemption has always applied to all white men. After all, A.J.’s grandfather and great grandfather were white. Were they exempt too?

One hundred twenty-five years ago in America, if your name was DeRosa, the answer would have been no. As an Italian immigrant you would have been denied the right to hunt and to own firearms and you would have faced fierce, even deadly, antipathy across the land. In fact one of the largest mass lynchings in American history was of 11 Italians in New Orleans, in 1891. Teddy Roosevelt actually described the event as “a rather good thing.”

And it wasn’t just Italians that faced discrimination. The Irish were also despised. Roosevelt wrote that “ . . . the average Catholic Irishman of first-generation as represented in this Assembly, is a low, venal, corrupt and unintelligent brute.” My Ukrainian and Icelandic ancestors faced discrimination when they first arrived in North America and Lisa’s French family can still face some resentment from some Canadians today.

But virulent anti-Catholic, Irish, Italian and French attitudes have all but vanished now. And Teddy Roosevelt is lauded—rightfully so—as a champion of conservation and ethical hunting practices. So history shows us that change is possible. The virus of discrimination can be defeated. But history also reveals that for some groups, like our black brothers, sisters, nephews and nieces, change can take centuries of painfully slow progress that only comes in fits and starts.

Yet there is hope. As millions march around the world, I believe we are on the cusp of another great change, one that will lead us to a time and place where our experiences as hunters are not coloured by the amount of pigment in our skin, but by the amount of love for the chase we hold in our hearts.

SUBSCRIBE to the AUDIO VERSION brought to us by: ESP – Digital Hearing Protection for FREE : Google | Apple | Spotify

I would politely say that you guys are contributing to the problem by bringing up the past. I’m very disappointed in you all and in your organization. You wanna end racism? According to Morgan Freeman (the actor), one way to get rid of racism at this point in time is to “QUIT TALKING ABOUT IT”. Maybe you should follow suit. Name ONE thing in America today that a black man cannot do that a white man can.

Thank you for your comment Jackson. I am sorry that you feel disappointed, but I am happy that you took the time to voice your opinion.

I should however mention that I may not be the best person to answer your question. I’m Canadian, and I’m white. The best thing I think I could do would be to ask some of my black friends in America to see what their answers are since they would have a better understanding of the issues than I do up here.

And while I respect Morgan Freeman’s point of view and admire his talent as an actor, I can’t agree with him on this issue. I stated the same thing to a fellow who recently posted that if we quit talking about gun rights, we’d get rid of the anti-gun issue. In any case, I am glad to see that you are at least willing to participate in the discussion and to finish your comment with a question that will keep it going.

I will post another reply after I’ve heard back from some of my black friends in American and they’ve shared their point of view.

Happy hunting!

Craig Koshyk