The Differences Between American and European Pointing Dog Tails

Whether a pointing dog’s tail is held level or at 12 o’clock is not particularly important—except for when it is.

What is the most important part of a pointing dog? For many, the answer is the nose. It is hard to argue with that position. After all, a dog can be perfect in every other way, but if it has a poor nose, it is useless in the field.

But what about the other end of the dog? How important is the tail? Obviously, compared to the quality of a dog’s nose, it means very little. Yet here we are, in the 21st century, with breeders on one side of the ocean refusing to breed to a dog on the other side. It’s not because they feel the dog has a poor nose, lacks desire, or any other truly important attribute. They won’t breed to it because they don’t like its tail carriage, action, and position on point.

American breeders of Pointers and Setters select for a 12 o’clock tail when a dog is on point and a “cracking” or “merry” tail while it runs. Most European breeders do the opposite. They select for a tail that is held level with the back on point and remains more or less motionless as the dog runs.

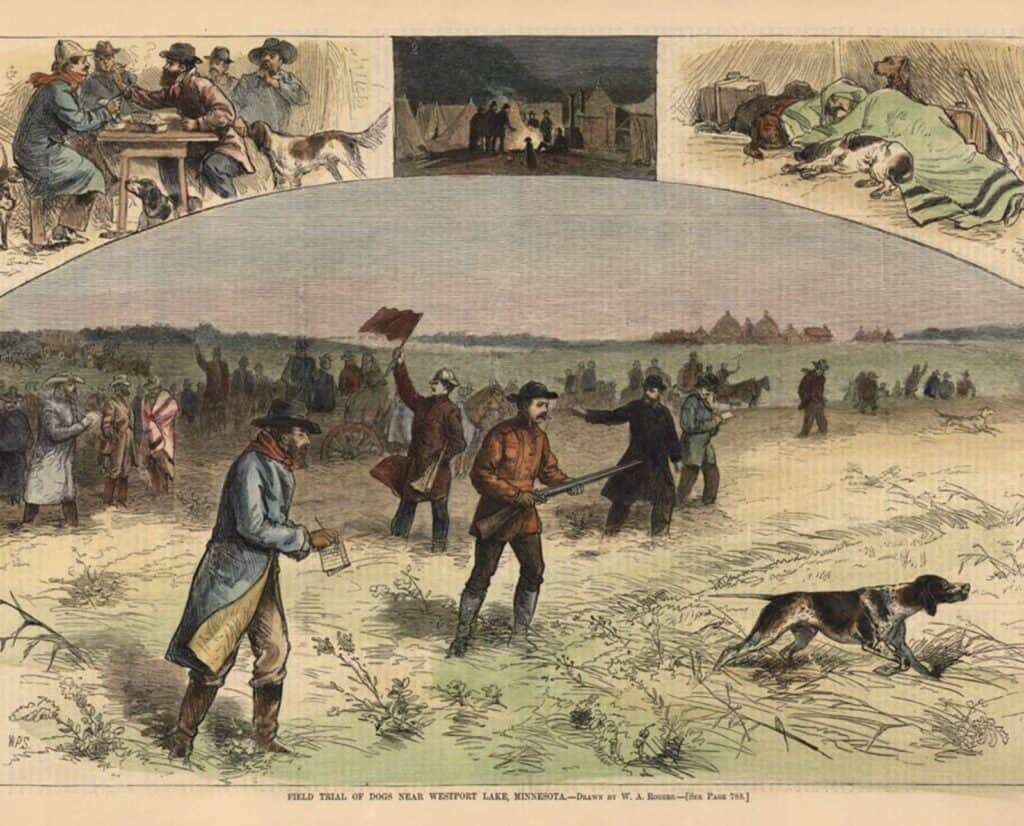

Historical Depictions Of Pointing Dog Tails

Looking through old illustrations of pointing dogs, it is clear that before the mid-1900s, pointing dogs were almost always depicted with a level tail or one held slightly above or below the back. What is believed to be the first illustration of Pointers in England is a painting of the 2nd Duke of Kingston-upon-Hull shooting over Pointers given to him by the King of France in 1725. All the dogs are shown with level tails or slightly raised tails. However, there are old images that show dogs pointing with high tails.

There is another painting from about 1800, attributed to artist James Barenger, that features a dozen dogs on point. Each one has a different tail position, from below the back, to level with the back, to nearly vertical.

Nevertheless, until the mid 1900s, the vast majority of pointing dogs, no matter where they were, pointed with a level or slightly raised tail. Almost all the classic illustrations show that a level tail was considered the height of style among hunters and judges. A classic painting by Charles Towne shows two of the most famous Pointers of the late 1700s, Colonel Thornton’s Juno and Pluto.

How the Difference In Pointing Dog Tails Emerged

Low or level tails were the norm in the U.S. until the middle of the 20th century. Of course, there were always a few dogs around that pointed with a high tail, but they were unusual and undesired. In describing the English Setter named Peach Blossom, a descendant of Count Gladstone IV, Joseph Graham wrote that her tail position on point was “peculiar” and included a photo of her on point in his book, The Sporting Dog, with the following caption:

Champion Peach Blossom…is the most typical living representative of the Count Gladstone IV blood; and because she represents in its extreme form the small, compact, high-strung field-trial Llewellin which has been for years a subject of controversy among the setter men. In the kennel she is an affectionate pet, vivacious and intelligent. In the field she is dashing and brilliant. Her peculiar carriage of tail on point is shown in the photograph, taken by the author.

By the early 1900s, attitudes towards a high tail began to change among field trial enthusiasts in America. Hunters understood that the game birds they most desired—quail and grouse—were usually found in thick, tall cover where it was difficult to see a dog on point.

“A great deal of quail shooting is done in cover which makes it difficult to keep a busy dog in sight,” wrote Joseph Graham. “Judging from my own observation, I should say that four-fifths of the work dogs do on quail is in cover of that sort.”

Increasing A Dog’s Visibility In The Field

What could a hunter do to make a dog easier to see? The first, most obvious solution was to breed for dogs with more white in their coats. Graham wrote that “In the corn-fields and thickets a dog of prevailing white color is much more readily kept in view.” He also suggested that hunters stop selecting and training dogs to “drop” on point.

Graham described a dog named Sure Shot whose coat and pointing style were problematic in field trials because he was “so heavily ticked that he is almost a dark gray. He drops on point. In public trials his handler is always nervous lest he get out of sight, drop on birds and be thrown out by the judges before he can be located.”

Finally, Graham also thought that a high tail—he called it a “high flag”—would make a dog easier to see in heavy cover. “…The high flag has a decided utility value to the sportsman,” he wrote. “A dog which carries its flag high will nearly always point with high head…As a guide to the eye it comes to be regarded with indulgence if not with decided favor.”

Graham first describes a high flag as “unfashionable” but later explains that “a man learns after experience to rather fancy the up-right position and high flag.” And he was right. Before long, breeders started selecting specifically for high tails, even though they remained unfashionable for years. In fact, rumors circulated that some Pointer breeders even crossed to hounds to get higher tails.

High-Tailed Pointing Dogs In Field Trials

In the 1920s and 30s, several high-tailed dogs began to win trials, despite the fact that most judges still preferred a lower tail. In his book, Bird Dogs and Field Trials, Jack Harper describes a conversation with Mack Pritchette, a well-known handler who had been in the game for decades. Harper asked him if the dogs running then (around 1932) were more stylish and had higher tails on point compared to dogs at the turn of the century.

“…Higher tails had become more fashionable and dog owners would always try to get the highest possible point for taking pictures,” Pritchette said. “Before, level tails were more in fashion, especially at the National where Mr. Ames presided, and dog handlers then would push their dogs’ tails to a lower level or wait until they were tired to make a picture for publication.”

Harper then names a number of dogs that, in his view, were the source of higher tails in the modern age. He wrote that Seaview Rex, a Pointer born in the early 1920s, may have been the first champion to have what eventually became known as a “12 o’clock tail.” However, since many of the old-school judges still considered high tails a fault, Seaview Rex never won the National Championship.

Seaview Rex

Writing in Gundog Magazine, John Criswell explained:

…[Rex] pointed with his tail straight in the air. He ran with it high and cracking—much in contrast to other dogs of the day—the dogs that Mr. Ames and his fellow judges elevated to the National Championship. In spite of the Ames’ theories, the new style caught the fancy.

Handlers, as well as owners, fell in line, and hunters decided that it was more attractive to see a dog standing there in the woods with his tail up and intent, than at back-level. Some didn’t care much about that part of the dog and still don’t. They only care about whether he finds much game and will stay put until it is flushed.

As field trials divided into “all-age” and “shooting dogs” and there were more and more of both, loft of the tail has become an easy way for some judges to distinguish what they like and what they don’t. It’s easy and obvious.

But how did so many get so high so soon when the Pointer was really a level-tail dog?

There have been reports in American Field that Seaview Rex was from a dam that was at the time unregistered. And, stories abound about the introduction of the hound to raise the tail in this line of Pointers. It is obvious from the high, curving carriage that the stories have foundation in fact. Was it on the east coast, or was it in plantation country of Georgia and Alabama? There is no documentation as to where and when—just the obvious change that it did happen.

I agree with Mr. Criswell and believe that an infusion of hound blood in America in the early 1900s probably did play a role in raising the Pointer’s tail. But it is quite possible that the trait also came from crosses to Setters.

High Tails In Irish Red Setters

By the 1950s and 60s, high tails in Pointers and Setters had become a must-have at the highest levels of field trial competition in America. They were so important that when Ned LeGrande attempted to breed competitive Irish Red Setters, he realized that he needed more than just a similar range, speed, and desire of the top-notch dogs on the circuit. If he wanted to win, his dogs also needed a 12 o’clock tail. And to get it, he’d have to cross high-tailed English Setters into his line of Irish Red Setters.

“During the late forties and early fifties when I used to spend a lot of time, especially nights, hanging around Rusty Baynard’s gasoline station, the Red Setter was then a pretty common bird dog,” wrote LeGrande. “Herm David, too, used to join us when he was in town, and the three of us used to talk, and dream, by the hour about Red Setters with high tails that would point early, break as derbies, and be able to run with, and whip the pointers in field trials. The Red Setter enthusiasts of today can’t realize how impossible those goals seemed in 1949.”

Today, Europeans Prefer “Traditional” Tails And Americans Prefer “12 O’clocks”

A high tail on point is the norm for almost all breeds of pointing dogs in North America today. Look at any photo from the last 75 years showing the winners of any major field trial for any pointing breed in America. You will see dogs lined up with handlers holding their dog’s tail in a 12 o’clock position, even if the dog is a Brittany with a stubby tail only two inches long.

I asked field trialer and writer Craig Doherty about why high tails came to be popular in trials. He wrote:

I can almost guarantee you what happened. Someone showed up at a field trial with a dog with a high tail when that wasn’t in fashion and beat all the low-tailed dogs. Wanting to win, others bred to that dog and more high-tailed dogs found their way into the money. Before too long, people who didn’t really understand what was going on thought you needed a high-tailed dog to win, so they bred to more high-tailed dogs. Now, if your dog doesn’t have an almost perfect tail and posture on point and an eye-appealing gait, you might as well stay home.

Today, the high tail has become so common in America that many see anything lower as unfashionable. In Europe, the opposite is true. Europeans prefer a traditional tail position on point. They want to see it level or only slightly raised when the dog is on point. A dog with a 12 o’clock tail would be seen as a curiosity among hunters there and would be at a distinct disadvantage in a field trial.

When I first began traveling there to take photos for my first book, Pointing Dogs, Volume One: The Continentals, I would bring a portfolio to show breeders and hunters what sort of work I do and what kind of images I was trying to get. When I got to the shots of North American-bred Pointers and Setters, I was surprised by my European friends’ reactions to them. Most of them had no idea that in North America, the preferred position of a Pointer or Setter’s tail is at 12 o’clock and were shocked to see it. One fellow even accused me of photoshopping the tails like that. But he was gobsmacked when I explained that the images were not photoshopped.

He then turned to his friend and said, “Hey, come look at these photos! You won’t believe it. I think they give their dogs Viagra!”

My View On Pointing Dog Tails

I have a theory about how and why high tails became so important in North America. It is long, convoluted, and probably nuts, but let me attempt to lay out a Reader’s Digest version.

If you could hold a huge stack of American Field magazine covers from the very first edition up to say, 1980 in one hand, and use your thumb on the other hand to make a sort of flip book animation of the photos on the cover, you would see the dogs’ tails go from 9 to 10 to 11 o’clock and finally to high noon.

But you would also see something else. Setters dominated the covers in the early years, but they eventually gave way to Pointers. Why? What advantage did Pointers eventually gain over Setters? and what the heck does that have to do with tails?

Setters Versus Pointers

While there are probably several answers to the first question, the one I’ve gotten most often from experts and written sources is that Pointers typically mature faster and can handle a lot of pressure early on. As field trials became more popular—and the money involved increased exponentially in the early to mid-1900s—American breeders, trainers, and handlers began to prefer Pointers. They broke out earlier, won earlier, and were easier and less expensive to train and campaign.

Tail Positioning And Emotional States

What does that have to do with tails? Two things. First, field trials aim to identify dogs that have many of the natural qualities we seek. Of course, they need to be very well trained, but we want to avoid seeing any obvious signs of all that training lest we judge them as overtrained or robotic.

One way we can assess a dog’s emotional state is by looking at its tail. A high tail is seen as a mark of confidence and a low tail as a sign of fear or anxiety. High-tailed dogs are considered proud, like an athlete raising its arms as it crosses the finish line. Low-tailed dogs may be seen as cowed, submissive beasts unworthy of respect.

So what happens if a naturally high-tailed dog lowers its tail as its handler approaches it? Everyone would see it as an indication of heavy-handed training and it would reflect badly on the owner and handler. So, today, in America, once a dog is on point with a 12 o’clock tail, it should hold that position for as long as it takes for the handler to pass in front of it, stomp around to flush the birds, and fire a shot. If it doesn’t keep its tail high, its chances of winning are nearly zero.

Did breeders and trainers—knowingly, or unknowingly—begin to select for dogs that held their tails straight up no matter what? Did they reinforce that position by training their dogs to hold it even if, on the inside, the dog is cowering?

The Ears Don’t Lie

Now, before you start calling me crazy, consider another aspect of a dog’s body language that communicates its emotional state: the positioning of its ears.

When a dog is afraid, lacks confidence, or is intimidated, it pins the ears. It holds them close to the skull, away from the muzzle and can even grimace a bit with lips pulled tight and towards its cheeks.

So can a dog’s confident, proud tail be betrayed by pinned ears? A quick Google image search reveals that the answer is a resounding yes. You can easily find images of dogs on point with their tails standing proud but with ears pinned back. Basically, the tail is saying that the dog loves the trainer or handler and has no fear of him, but the ears say the opposite.

My Theory

Here is my wild theory of why, at least in part, high tails are now a must in North America. By selecting for and training dogs to always have a high tail, no matter what, we can mask any negative effects that a high-pressure training regime can have on a dog. But we can’t mask it completely. To a close observer, the ears can give it away.

I believe that, at some point, as trainers needed to get better, faster results in training from an ever-growing number of dogs, they realized that there were additional benefits to a high tail beyond seeing a dog at greater distances. If a dog has a high-no-matter-what tail, you could put a ton of pressure on it during training, and no one would be the wiser.

Of course, modern training methods are light years from where they used to be. The vast majority of dogs with high tails today are confident and proud, and their trainers never train them with a heavy hand. But in the past, that was not the case. Old-school trainers could be extremely hard on their dogs, and they got the results they wanted, including a high tail, no matter what.

How important is a dog’s tail? Not very, except when it is.